– Norsk tekst kommer –

Unlearning Optical Illusions is a project in several iterations that combines elements from the history of Western science with the history of wax resist textiles. The project is a reflection upon seeing, as in the sense of sight and as metaphor for knowledge.

Starting from the idea that the eye is not a ready shaped and passive receiver, but an active and subjective sense, the project started with questions concerning how my environment contributes to ways of seeing and interpreting the world. The questions were such as: If seeing is something that I have learnt, can I unlearn ways that I have been taught to see? Is visual perception shaped by my environment, including my culture, as some scientific studies have proposed? And how might western science and globalisation have shaped my ways of seeing?

The project includes four iterations: The first is an illustrated essay entitled Unlearning Optical Illusions in my artist book Unseeing (2013). The second version of the project is a series of 7 photographs with accompanying texts (2014). The third is a textile installation (2015). The fourth is a series of textile sculptures (2018). In addition, the design collective HAiK w/ made use of the printed textiles in their project Interpretations (2017).

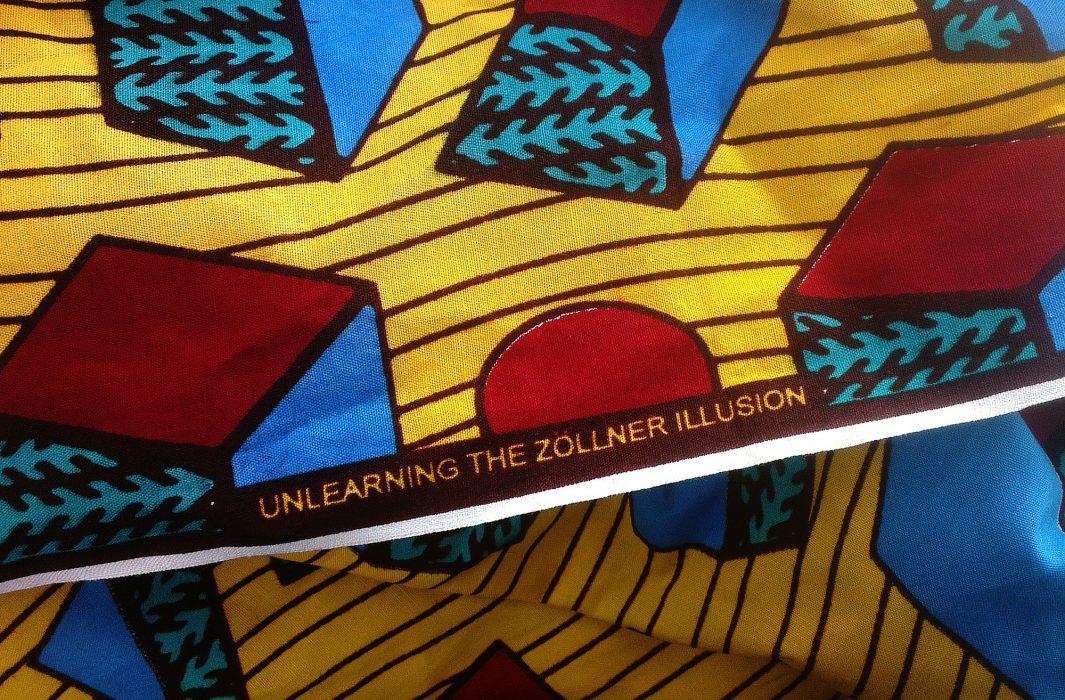

Recurring in these works is a series of pattern designs that has figures known as classical geometrical optical illusions as part of the design. The patterns are designed by myself, and were produced as wax resist prints by the textile printing company GTP in Ghana for the third iteration of the project.

The juxtaposition of form and references in the work is associative, and is based on my reading of two complex and contradictory narratives concerning interpretation and visual expressions.

Geometrical optical illusions has been used as tools in Western scientific studies of perception in order to measure how humans interpret visual stimuli. In the 19th and 20th century, several cross-cultural studies examined susceptibility to illusions. A number of studies involving the Müller-Lyer illusion concluded that the illusion is not universal, as participants saw the figure as illusion to varying degrees depending on their culture. The explanations for why this might occur are many and conflicting. Some of the explanations points to differences in the visual environments of the participants, where the ones living in urban environments saw the figure as illusion to a greater extent than others.

One example is an often cited study from 1963 by Campbell, Herskovits and Segall. What followed is known as the carpentered world hypothesis, a concept that might bring to mind ideas of a western “built” world as a measure and opposition to other cultures. According to the hypothesis, the North American and European participants perceived the figure as an illusion because they lived in environments with straight lines and right angles, therefore interpreting the geometrical figure as if it was three dimensional representation. The East African and Southeast Asian participants saw the figure as illusion to a lesser degree, and the hypothesis suggested this was related to their living environments with few straight lines and predominantly round buildings. Similar theories have been proposed, but the argument is contested, and is challenged by other explanations for why cultural variation in perception might occur.

Wax prints are industrially printed textiles also known as batik, wax resist print, African print, Java Print, Ankara, Dutch Wax Print, Hollandaise, Real English Wax, among many other names. Such textiles are amalgams of artistic traditions. Commonly in use in West Africa, wax prints combine traditional and contemporary styles, and their aesthetics and symbolic meanings are part of social dynamics in the societies in which they are in use.

As industrial products that can be traced back to Indonesian batik crafts, wax prints are also carriers of complex histories of cultural appropriation, globalisation and colonial trade. With the Industrial Revolution and Dutch colonial trade in the 19th century, Indonesian batik was copied and put into industrial production in Europe. The purpose was to sell the products back to the country of origin. This failed, and the European textile industry therefore tried to find other markets for the products. Indonesian batik was already known in West Africa at the time, and by the end of the 19th century, the European and especially Dutch textile industry began manufacturing directly for the West African market. Wax print production later also established in West Africa, especially during the independence era in the 50’ and 60’s. Parts of the industry is still in Europe, with competition from manufacturers in Southeast Asia, mainly China. Through multiple relocations and transformations, wax print designs have developed into new forms and aesthetics.

For more about the project and the history of wax prints, please see Unlearning Lessons: A conversation between Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh and Toril Johannessen (2016) and Textiles, Taxes & Translations by Jessica Hemmings (2017).

Produced with support from Arts Council Norway, City of Bergen, NBK/Vederlagsfondet and Ingerid, Synnøve og Elias Fegerstens stiftelse.

-

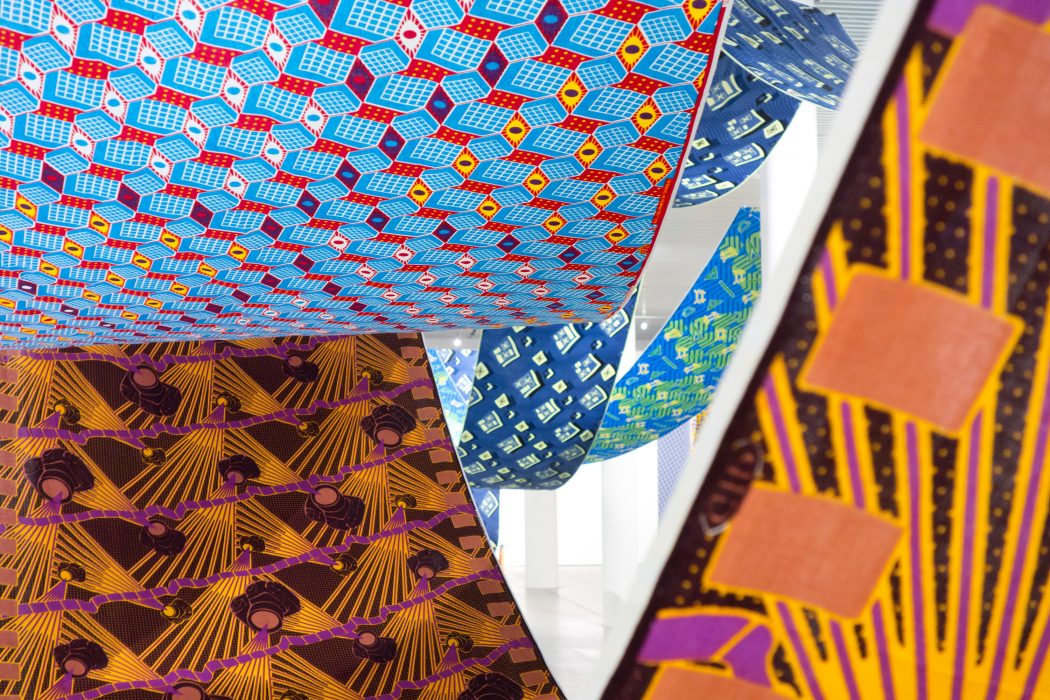

Unlearning Optical Illusions (III) (2015). Printed textiles (wax print on cotton), steel racks. 5 designs x 1,2 x 1100 meter. The printed patterns are 5 of the 7 designs that appear in the two first iterations of the project. Colours and details in the designs are adjusted to fit the particular printing process, so the patterns have changed slightly from the designs in Unlearning Optical Illusions (I) and (II). The textiles are printed by GTP in Tema, Ghana.

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (III), installation view, Vigeland Museum. Photo: Christina Leithe Hansen.

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (III)

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (III)

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (II), (2014). 7 photographs, texts and lines on the floor. Photographs of folded textiles accompanied by sheets with texts on optical illusions and wax prints. An instruction to the works explains to the viewer how to find the blind spot in their eyes in order to - literally - not see the text sheets and instead focus on the photograph

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (II), installation view, Trondheim Art Museum. Photo: A. Solberg.

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (II), installation view, AROS Art Museum, Aarhus.

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (I), book and wallpaper, AROS Art Museum, Aarhus.

-

Unlearning Optical Illusions (II), Unlearning the Hermann grid Illusion, photograph, 170x120 cm.